Earthquakes operate on a different timeline than most infrastructure planning. In the Pacific Northwest, the Cascadia Subduction Zone produces massive seismic events every 300 to 500 years, and by many estimates, the region is already deep into that cycle.

“At this point, it’s not really a question of if,” said Brant Foster, PE, Senior Project Manager and Design Lead at Century West. “It’s just when.”

For Portland International Airport (PDX), that reality presents a critical challenge. Located adjacent to the Columbia River, the airport’s existing runways are highly vulnerable to liquefaction and differential settlement during a major earthquake. If a Cascadia event were to occur today, the airport would almost certainly be forced to shut down, cutting off one of the region’s most viable lifelines for emergency response and recovery.

The Seismically Resilient South Runway project is designed to change that.

A Runway Built for Recovery

The project’s goal is simple and profound: to construct a runway that remains usable following a major earthquake.

“In a post-earthquake scenario, you don’t need a full airport,” Foster explained. “You need a place where aircraft can land, unload supplies, turn around, and take off again.”

The resilient South Runway is designed to provide exactly that. While it will not immediately connect to a full network of taxiways or gates after a seismic event, it will allow emergency aircraft, including those operated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the National Guard, and other response agencies, to bring critical supplies and personnel directly into the Portland region.

“That’s the difference,” Foster said. “Without this, PDX isn’t an operational airport after a major earthquake.”

The “Magic” Is Below the Surface

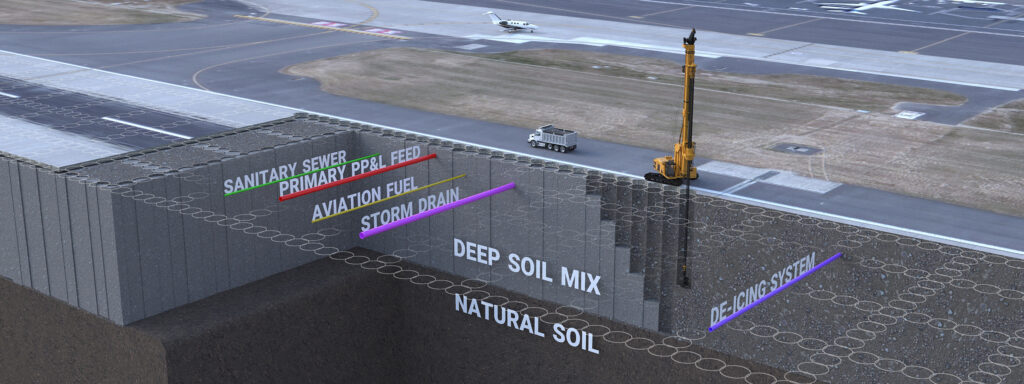

While the reconstructed runway will look much like any other runway when complete, what sets this project apart is what lies beneath it.

The ground stabilization approach was informed by extensive geotechnical investigation and analysis led by Geotechnical Resources, Inc. (GRI), who provided the initial geotechnical report for the project. Through multiple phases of subsurface exploration, laboratory testing, and seismic modeling, GRI evaluated liquefaction risk and post-earthquake settlement behavior and developed performance-based recommendations for stabilizing the soils beneath the South Runway. Their work provided the technical foundation for how and where ground improvement would be applied.

The design relies on deep soil mixing (DSM), a ground improvement technique that involves injecting cement into the ground to create a grid of cement columns below the runway surface. These columns form a stabilized foundation beneath the roughly 7,500-foot-long runway. The DSM grid allows the runway to move as a single, unified structure during seismic shaking, much like a boat floating on water.

“It might settle, it might rotate a little, it might slide slightly,” Foster said. “But it stays flat and straight. And that’s what makes it usable.”

Without this approach, the runway would be subject to unpredictable cracking, vertical drops, and surface deformation. Those conditions would render it unusable for aircraft operations.

Why the South Runway, and Why 7,500 Feet

Selecting the South Runway for seismic hardening was a deliberate decision informed by years of geotechnical research. Compared to the North Runway, the South Runway sits farther from the Columbia River, reducing the risk of lateral soil movement that could cause a reinforced runway section to slide off its foundation.

Even so, the design team had to make careful decisions about how far the resilient section should extend.

“At a certain point, the soil conditions change enough that the solution becomes exponentially more expensive,” Foster said. Extending the DSM foundation deeper, to bedrock nearly 150 feet below the surface, would have driven costs into the billions.

“At 7,500 feet long, you can safely land the aircraft that matter most in recovery scenarios,” Foster said. “Beyond that, the cost just doesn’t pencil out.”

Leadership Before Disaster Strikes

While the engineering behind the project is complex, both Foster and Matt MacRostie, PE, Century West’s Executive Vice President and Project Manager, emphasized that the real catalyst for the project was the Port of Portland’s willingness to act before disaster strikes.

In addition to GRI, the project has also relied on close collaboration among a multidisciplinary team of consultants, including Jacobs, who supported early resiliency planning efforts and led utility design efforts, and Shrewsberry & Associates, who assisted with construction safety and phasing strategies to help maintain airport operations during the extended runway closure required for construction.

“This is a massive investment that is focused entirely on preparedness and recovery,” Foster said. “It’s not about day-to-day operations. It’s about being ready for an event that could fundamentally change the region.”

MacRostie agreed.

“The Port has taken on the responsibility of doing something proactive,” he said. “They’ve recognized what recovery will actually require, and they’re acting on it.”

That foresight is critical. After a Cascadia event, traditional construction resources such as concrete plants, asphalt plants, and transportation corridors may be damaged or unavailable. Waiting to rebuild after the fact could mean years without functional air access.

“We’re talking about saving lives,” MacRostie said plainly. “Getting medical supplies and emergency personnel in and reducing the strain on a city that’s already dealing with a catastrophe.”

Designing What Hasn’t Been Done Before

When complete, the PDX Seismically Resilient South Runway is expected to be the first of its kind in the United States and only the second in the world. The only comparable project, a resilient runway in Japan, proved its value during the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, returning to operation within weeks.

Still, neither Foster nor MacRostie expects this approach to become commonplace overnight. “This isn’t something every airport needs,” Foster said. “It depends entirely on seismic risk.”

However, the project may influence how airports in high-risk regions think about resilience, not just for runways, but for utilities, power systems, and emergency operations as a whole.

“For PDX, the runway is the first step,” Foster said. “It opens the door to thinking about taxiways, utilities, and self-sufficient power systems. Recovery is a system, not a single asset.”

A Career-Defining Project

For the Century West team, many of whom have worked at PDX for decades, the project carries special meaning.

“I helped design this runway in its current configuration back in 2011,” Foster said. “It was set to last 40 years. I never thought I’d work on it again.”

Yet seismic resiliency demands starting from the ground up, literally.

“To build resilience, you have to remove what’s there,” he said. “There’s no shortcut.”

MacRostie echoed the sentiment, emphasizing that while the project is significant for Century West, it remains firmly rooted in service to the region.

“We’re honored to be part of something that matters this much,” he said. “But the credit really belongs to the Port for stepping up and leading.”

Looking Ahead

Final design for the Seismically Resilient South Runway is underway, with construction expected to follow once funding is secured. When completed, the runway will stand as a critical piece of infrastructure designed for resilience when it’s needed most.

“It’s not about hoping the earthquake doesn’t happen,” Foster said. “It’s about making sure we’re ready when it does.”